Abstract

This research provides insights into how targeted and non-targeted customers perceive firms’ marketing tactics. Important implications exist regarding how targeted and non-targeted customers perceive the influence of marketing tactics and, accordingly, how firms handle them. A multiple-phased study approach involved exploratory interviews, pilot tests and the main survey, which employed a self-administered questionnaire. As a stage one research, initial results offer a perspective on how marketers can maintain and enhance the two key customer groups in a unified framework. Targeted customers respond more strongly to service quality and communication, whereas price is more important to non-targeted customers. It is hoped that the study may serve as a framework for future studies to contribute to the literatures on customer management and, in particular, on how marketers should manage targeted and non-targeted customers with their tactics. Identifying the different perceptions of targeted and non-targeted customers should help marketers develop more effective segmentation and customer relationship management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The key principle in target marketing is to meet customers’ individual needs and to direct firms’ marketing efforts and attention to customers who they estimate will yield the most profit over their lifetime, whereas discarding unprofitable customers1, 2, 3. Marketers have long pursued this approach successfully by facilitating customized solutions on a one-to-one basis, most notably in segmentation and CRM schemes.4, 5

Prior research distinguishes between the targeted and non-targeted customers6 where non-targeted customers is said to get ‘the short end of the stick’. This means that either pay more to receive the same or receive less even though they paid the same price (compared with the targeted customers). Despite the common use of the terms ‘targeted’ and ‘non-targeted customers’, surprisingly, few studies have examined the two groups’ differing perceptions and their views on marketing tactics in a single study.

The purpose of the study is to deepen our understanding of the perceptual differences between the targeted and non-targeted customers and their characteristics, feelings and behavior. The study attempts to explain the differential impact of marketing tactics on the two customer groups, suggesting that certain marketing tactics may have a stronger impact on one group over the other. Using retailing and a low-involvement purchasing context, this study develops a better understanding of the two groups with regard to their perceptual differences. Understanding customers’ perceptions will have implications for how marketers should manage their customers more effectively, in this case as part of a larger segmentation and relationship management scheme.7, 8 Thus, the present study investigates the following questions: (i) What are the perceptual differences between targeted and non-targeted customers with regard to marketing tactics? and (ii) Which tactics impact on the customers most – that is, which tactics do the customers respond to more strongly than others? Theoretical foundations from existing literature, including equity theory, attributions theory and the principle of reciprocity, inform the study. In this study, targeted customers are conceptualized as those who receive the firm's attention and enhanced marketing offers, whereas the non-targeted customers are identified as those who are ‘disadvantaged’ and do not explicitly receive any particular marketing offers.

The next section examines the roles of the various marketing tactics, followed by an explanation of the methodology and a presentation of the study's findings. The following section then explores how marketers can manage the two customer groups. Theoretical and managerial implications are then discussed.

MARKETING TACTICS

The first step of this research is to identify the variables that may be sources through which customers evoke perceptions about a firm. To establish these variables, the literature reveals several constructs that marketers have used to influence their customers, such as the traditional 4p's. However, conceptualizing and operationalizing the marketing concept is difficult because of the many definitions of marketing. It is acknowledged that there is challenge in selecting marketing tactics in that any definition of marketing is contingent on the level at which an organization practices it or on what the researcher believes about the correct level of marketing.9 Although it is recognized that many conceptualizations of marketing exist, this study focuses explicitly on marketing tactics, as varying use of tactics influence customers differently, suggesting that customers’ specific perceptions vary depending the impact of certain tactics.10 For marketers, this has stark implications as to how they can identify appropriate marketing tactics to satisfy different customer groups, here both the targeted and non-targeted customers.

Drawing from the literature on customer management, this study employs concepts from prior research to identify the factors that differentiate the impact of marketing tactics on the two groups. Following Berry's11 three levels of relationship marketing (pricing incentives, social bonds and structural solutions to customer problems), the PPM (push, pull and mooring) model of migration,12 the RMT model of relationship marketing tactics13 and the CRM offering model,14 this study identifies five marketing tactics as determinants and factors that influence buyer–seller interactions.

Thus, the current framework includes pricing offers, product and service quality, marketing communications, customization, and reputation.13, 14, 15 These constructs capture the mechanisms of the interactions and relationships between a customer and a firm,13 and are fundamental sources to understand the targeted and non-targeted customers’ perceptual differences. They also reflect important aspects of marketing in understanding and managing customers on an individual basis.

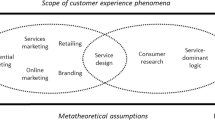

Overall, this study determines two areas that require further research: (i) the differential influence of marketing offerings (price, service quality, communications, customization and reputation) on targeted and non-targeted customers and (ii) the unification of diverse research streams to explain the underlying theories (equity theory, attributions theory and the principle of reciprocity) pertaining to the behavior of these two customer groups. Figure 1 provides a conceptual model for understanding the influence of marketing tactics on targeted and non-targeted customers.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Equity theory16, 17 provides a framework for conceptualizing customer behavior of the two groups. As a theory from the behavioral psychology literature, equity theory is incorporated to help explain the perceived levels of influence of marketing tactics on the targeted and non-targeted customers.16, 18 Equity theory postulates that people in social exchange relationships compare their inputs into the exchange with their outcomes from the exchange. It suggests that different consumer perceptions arise when a person compares an outcome with a comparative other's outcome. This reference may be another person, a class of people, an organization, or him- or herself in relation to past experiences.18, 19, 20 Inequity occurs when the perceived inputs and/or outcomes of an exchange relationship are psychologically inconsistent with the perceived inputs and/or outcomes of the referent.18 On perceiving inequity, a person is motivated to restore equity or balance. Previous research uses equity theory to explain job motivation,18 buyer–seller relationships ,17 satisfaction,21 complaint behavior,22 price fairness,20 customer revival23 and CRM.14

At the center of equity theory in job motivation is the ‘underpay/overpay’ framework.18, 24 This framework suggests that though equal pay represents the balance, situations of inequality also occur, such as the case with underpaid and overpaid employees. This underpay/overpay continuum reflects the two forms of inequity in equity theory. The current study argues that in a broader marketing context, the equity model also allows for non-targeted customers (analogous to underpaid employees); that is, they get the ‘short end of the stick’. Conversely, the targeted customers are analogous to overpaid employees. Subsequent perceptions and behaviors of these customers in the two situations could reflect modes of inequity reduction to restore balance.

Although equity theory is an overarching framework for the current study, there are also other theories, which are used to justify the conceptual framework and hypotheses. The principle of dual entitlement suggests that people have expectations about aspects they are entitled to because of their situation.25 For example, a loyal customer may claim that they should receive added value offers because of his or her perceived entitlement due to their patronage and history.20 In addition, considerations to understanding the perceptions are also given to the attributions a person may infer toward a provider.26 Attributions theory indicates that people likely search for causal explanations for an event when the event is surprising and/or negative.27 And lastly, using norm theory,28 thoughts are given to a person's knowledge, beliefs and social norms in a society.29

Thus, on one hand, the targeted (or overpaid) represents an advantageous position, and a firm strives to keep and maintain customers in this state of mind. On the other hand, the non-targeted (underpay factor) tends to motivate customers to seek justice/balance, including that pertaining to negative behaviors. Thus, a firm needs to develop these customers and enhance its tactics when possible.

INFLUENCE OF MARKETING TACTICS ON TARGETED AND NON-TARGETED CUSTOMERS

This study focuses on the tactics of the marketing domain. This customer-facing level is important in considering consumer perceptions because the tactics the firm employs influence customers’ perceptions of that firm. In other words, customers’ perceptions of a firm are developed from these tactics because they are the customers’ contact reference point with the firms. The choice of marketing tactics in this study has reflected a need for a realistic reflection of marketing at the customer-facing level. Each of the five marketing tactics and offerings – namely, service quality, pricing, communication, customization and reputation – transcends every marketing process, and thus they are major factors in maintaining and enhancing buyer–seller relationships.

Price

This study proposes that price has a greater effect on customers not targeted by the firm than customers targeted by the firm. The overall tenet is that non-targeted customers (characterized by feelings of disadvantaged inequality) feel disappointment and unfairly treated by a retailer's non-targeted treatment30 and, as such, will seek monetary compensation.20 Non-targeted customers may also be more price conscious and more motivated to spread negative word of mouth to vent their discomfort if they cannot ‘get back’ at the retailer.31, 32 Sinha and Batra33 find that price increases customers’ price consciousness when they feel unfairly treated and that those buyers tend to focus on the monetary sacrifice.

Thus, price should have a greater effect on non-targeted customers than targeted customers because of their belief that the retailer is treating them unfairly due to the monetary sacrifice of paying more than targeted customers. Equity theory further explains the theoretical rationale; the non-targeted customers will search for better prices to compensate for being ‘underpaid’ or undercompensated. That is, when a customer discovers that a comparative other received a better price, he or she may be motivated to obtain lower prices. In other words, the non-targeted customer aspires to receive better prices and is more concerned about prices.

Attributions theory also supports this proposition; that is, the non-targeted customer may be more likely to search for causal explanations for an event when the event is surprising and/or negative,27 such as a price increase. Thus:

Hypothesis 1:

-

Of the two customer groups, non-targeted customers respond to price more strongly than target customers.

Service quality

This study postulates that service quality has a greater effect on targeted customers than non-targeted customers. Because targeted customers receive ‘the long end of the stick’ (for example, better service), they incur a favorable position in the firm and therefore benefit from better and more personable service. In contrast, non-targeted customers are in a disadvantageous position and therefore experience poor service, which results in dissatisfaction with the service. They consequently do not respond to the service in the same way as if the service had been good. For example, a customer who experiences poor service may be reluctant to obtain more service from the provider and therefore will not engage further with that provider. When a customer discovers that a comparative other received better service, he or she may be even less inclined to engage in the service any further. In other words, the non-targeted customer does not aspire to have better service from the provider and remains status quo by ignoring the service. In serious cases, the customer may simply leave the exchange relationship to avoid future poor service.

In addition, according to the principle of dual entitlement, the targeted customers believe that they are more entitled to the quality service and expect more benefits because of their advantageous position and adaptation to the level of service already received. Indeed, adaptation level theory34 suggests that exposure to earlier stimuli serves as a frame of reference by which later stimuli are judged. These stimuli form a person's unique adaptation level. Thus:

Hypothesis 2:

-

Of the two customer groups, targeted customers respond to service quality more strongly than non-targeted customers.

Communication

Communication is essential in sharing information and coordinating behavior in buyer–seller relationships because communication increases the exchange dialogue and creates personalized customer experiences.35, 36 Information reciprocity is the notion of customers giving a firm their information in return for customized offerings and is at the center of marketing because it creates a win-win situation for both the firm and its customers.35

This study proposes that marketing communications has a greater effect on targeted customers than non-targeted customers. The reasoning is that targeted customers are in a beneficial position and experience benefits by communicating with the retailer.37 Thus, they also respond more to further communication. Non-targeted customers are in a disadvantageous position and therefore do not receive enough attention or value offers from the retailer. In turn, they refuse further dialogue with the retailer because of their negative experiences.

The principle of reciprocity further supports this proposition; that is, balance occurs when exchange partners give information and receive benefits in return.38 Because the targeted customer has received benefits in return for his or her information, he or she will continue to be involved in communication with the retailer; in contrast, the non-targeted customer, who has also given the same amount of information but has received fewer benefits, will not respond to further communication. Thus:

Hypothesis 3:

-

Of the two customer groups, targeted customers respond to communication more strongly than non-targeted customers.

Customization

Customization or personalization pertains to offering special deals (targeted promotions) to specific groups of customers or tailoring offerings to appeal to specific sets of customers.6, 39 Customization reflects the practice of one-to-one marketing through the use of mass customization.40

The effect of customization is greater on targeted customers than non-targeted customers because customization requires customer communication and involvement, both of which the targeted customers are engaged in because of their favorable position. In contrast, non-targeted customers may believe that they have not received a similar or equal outcome from their customized offerings and therefore will have feelings of disadvantaged inequality. They may not be engaged in any particular dialogue with the retailer because of these negative experiences. Equity theory suggests that when a customer discovers that a comparative other received more customized offers and targeted promotions from the provider, he or she may be motivated to develop the customization process further. However, the non-targeted customer may not aspire to receive better customized offers than the targeted customer, who already has a high level of customization/personalization.

The principle of dual entitlement further supports this proposition; that is, the targeted customers believe they are more entitled to the customized promotions and expect more benefits because of their advantageous position and adaptation to the level of service already received. Finally, according to norm theory,28 the targeted customers should be more involved with customization because they receive more favorable treatment than non-targeted customers. Thus:

Hypothesis 4:

-

Of the two customer groups, targeted customers respond to customization more strongly than non-targeted customers.

Reputation

This study proposes that non-targeted customers are more concerned with reputation than targeted customers. The rationale is that negative experiences lead to stronger impressions, and non-targeted customers already have such negative experiences. For example, a customer who has experienced incidents of dishonest behavior, unhealthy practices or conflicts of interest,41 may be more cautious and guarded against other providers exerting similar marketing practices or having similar reputations. The overall tenet here is that poor experiences result in a greater negative perception of the retailer's reputation. Consequently, the non-targeted customer is more aware of the retailer's bad reputation and may not respond to it in future purchases. Analogous to the way higher perceived price increases customers’ price consciousness for future purchases,33 a retailer's negative reputation leads the non-targeted customer to be more reputation conscious given his or her negative experiences. However, although the targeted customer may also be concerned about the firm's reputation, he or she may not be more concerned than the non-targeted customer.

Attributions theory further supports this proposition; that is, the non-targeted customer may be more likely to search for causal explanations for a bad or good reputation when the event is surprising and/or negative.27 If a retailer has a bad reputation for having long, slow and bureaucratic processes in dealing with customer requests, a non-targeted customer will seek to attribute such behavior and have negative inferences toward the retailer. Thus:

Hypothesis 5:

-

Of the two customer groups, non-targeted customers respond to retailer reputation more strongly than targeted customers.

METHODOLOGY

Research setting

The research for this study involves the retailing sector. Retail was found as the most applicable to the study of marketing tactics because the following conditions exist: (i) the firm wants to build a relationship with its customer; (ii) the firm makes extensive use of customization tactics; and (iii) other market-related criteria requiring the use of marketing tactics (for example, high competition, free market, availability of switching between firms).42, 43 The aim was to test theories through a natural and realistic setting, and the above factors comprise the chosen sector. The retailing sector environment enables marketing tactics and practices to flourish. This sector also guarantees that survey respondents have appropriate exposure to marketing tactics that are relevant to the study.

Data collection procedures

The present study is a stage one research and a first step toward a larger study. It adopted a multiple-phased approach to increase the similarity with the proposed comprehensive study. A three-stage process influenced the final design of the questionnaire, which was the main instrument for the survey: (i) exploratory interviews, to identify key issues that were relevant to understand the differences between the targeted and non-targeted customers; (ii) scale development from the existing literature; and (iii) pilot tests, which included checks for content and face validity before implementation of the main survey. For a broader understanding of the issues, the exploratory study obtained contributions from both a customer perspective and a firm perspective. Several modes of interviews were conducted, including face-to-face interviews, telephone interviews and e-mail inquiries. For the main study, the sample consists of consumers (students) who are regular shoppers at various retailers and managers from various retail organizations.

Before the main study, a comprehensive pre-test stage was conducted. This stage involved subjecting the generated pool of measurement items to a group of experts. A sample from the population of interest was used for this pre-study, in which each respondent checked whether the item measures were adequate, relevant and representative in measuring the constructs. The measures were selected by reviewing relevant dimensions and ensuring that all key aspects of the conceptual definitions were reflected in the item measures, to achieve reliability and construct validity. The different dimensions used for this study were chosen because of their relevancy in creating a realistic depiction of the marketing tactics, following the conceptualizations as mentioned previously. This step comprised both an item-trimming process and a final check for content and face validity before the main study.

For the survey, 143 questionnaires were distributed across a large UK university with the support of both lecturers and PhD students who gave the questionnaires to their students. It was estimated that as a stage one research, this was an appropriate sample. The sample was chosen conveniently across the campus and intercepted at various meeting points, such as in class, library and student café. It is acknowledged that a more comprehensive survey should be conducted in the future to enhance the validity of this study. Once the data were collected, a rigorous approach was applied to scrutinize and analyze the results from the main survey using descriptive statistics and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Data collected from the main study helped develop and purify the measurement scales using exploratory factory analysis (EFA) and validate the scales using confirmatory factory analysis (CFA). SPSS was used for the EFA, and LISREL was employed for CFA. To test the hypothesis, descriptive statistics were first used to create customer profiles of the targeted and non-targeted customers, followed by MANOVA tests to seek answers related to these customers’ perceptions of marketing tactics relevant to the study.

Measures

The items used to measure the variables were obtained by adapting existing measures from prior studies to fit the current research setting. All items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

The study adapted the following items: price perception,44 service quality,45 communication,46 customization47 and reputation.48 The targeted and non-targeted customers were measured following Xia et al's20 and Nguyen and Simkin's14 propositions that a buyer may have feelings of ‘advantaged inequality’ – which lead to feelings of satisfaction or even guilt and unease, even when the inequality is to his or her advantage – and feelings of ‘disadvantaged inequality’, which lead to feelings of anger or outrage when the inequality is to his or her disadvantage. Thus, targeted customers have feelings of satisfaction49 or guilt,50 and non-targeted customers have feelings of anger31 or outrage.51, 52 This is consistent with past studies, including Campbell,26 Xia et al20 and Lee-Wingate and Stern.53

RESULTS AND FINDINGS

Characteristics

Of the respondents, 48 per cent belong to the advantaged customer group and 52 per cent belong to the disadvantaged customer group. The respondents included shoppers and buyers from various retailers; they were ages between 18 and 60, urban, about equally male and female, highly educated and included students, PhD researchers and academics. The majority resides in the United Kingdom and have a household income of less than £30 000 per annum. Differences were found between the two groups’ preferred choice of marketing communications and promotion. It was found that friends (word of mouth) and television were the most preferred choice of both groups for receiving offers from retailers (see Table 1). Overall, the data show good variance for all the items measured.

Non-response bias

As responses were relatively low (143 respondents), the study ran tests for non-response bias by assessing the difference between early and late respondents. The early respondents constituted the first 75 per cent, and late respondents constituted the last 25 per cent of the questionnaires. The MANOVA technique compared the means of all manifest variables for early and late samples. The results from the MANOVA test of group means for all the variables show a non-significant difference between the early and the late respondents (P>0.05), indicating that non-response bias is unlikely to be a significant problem in this research. Table 2 shows the correlation matrix for all constructs.

Scale validation

Before the data could be used to test the hypotheses, they were subjected to a rigorous process to purify and validate the measurement scale items. Following the aforementioned data screening process, EFA was first carried out using SPSS and subsequently followed by CFA (EFA) using LISREL. The purified scales exhibited good model fits, significant path coefficients, and satisfactory reliability and validity. Table 3 shows the results of the CFA, including sample items, Cronbach's α, composite reliability and average variance extracted.

Validation of hypotheses

Before any hypothesis testing was conducted, the items used in the analysis were averaged to represent the dimensions of all the constructs according to Hair et al55 To compare the differences between the targeted and the non-targeted customers’ perceptions of marketing tactics in a retail setting, a comparison of the group means was carried out using MANOVA.

The Box's M test assesses the null hypothesis that the observed covariance matrices are equal across groups. The results indicate evidence of homogeneity of the variance–covariance matrices because the test was not significant at an α level of 0.001 (P>0.001). Levene's test of equality error of variances examines the null hypothesis that the error variance of the dependent variable is equal across groups. The results show that the homogeneity assumption has not been violated, that is, the population variance for each group is equal at P>0.05. Finally, the multivariate tests of significance reveal significant differences in perceptions of marketing tactics between the targeted and the non-targeted customers (P<0.05). This is shown in Table 4.

To test the hypotheses related to the targeted and non-targeted customers’ perceptions of the levels of influence of marketing tactics, an examination of the univariate F-tests for each marketing tactic was conducted. The test indicates which individual variable contributes to the significant multivariate effect. The results show that all constructs differ between the groups’ perceptions of marketing tactics, but only price, service and communication differ significantly across the targeted and non-targeted customers (significance is measured at an α level of 0.05). Table 5 provides the results of the hypotheses testing.

The results show a difference between the two groups in the level of perception of the various marketing tactics. The propositions state that targeted customers are influenced more by their perceptions of service quality, customization and communications than non-targeted customers. Of the three offerings, both service quality and communications were statistically significant at P<0.05, whereas customization was not statistically significant. The propositions state that non-targeted customers are influenced more by their perceptions of price and reputation. However, of the two offerings, only price was statistically significant at P<0.05, whereas reputation was not statistically significant. Thus, the results for customization and reputation indicate that the two groups of customers did not differ significantly in their perceived level of influence.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

According to prior research, firms must recognize the heterogeneity inherent in their customer base and treat those segments differently with regard to relevant marketing tactics.13, 15 This study provides conceptual and empirical support to advance understanding of the complex interactions between marketing tactics and the targeted (favored) and non-targeted (non-favored) customers in a single study. The findings show that these customers perceive the influence of marketing tactics differently. The authors acknowledge that when interpreting the results, it should be recognized that the present study is a stage one research and a more comprehensive study with a larger sample size should be conducted to verify the findings from this study. Nevertheless, the present study offer interesting findings, as discussed next.

This study reveals that the key agenda for firms is to recognize the uncertainties in managing various types of customers and to identify the factors that can help manage these uncertainties associated with developing and implementing marketing tactics. The findings from this research can equip managers with a better understanding of the two customer groups, so that they can deploy a better approach to their marketing tactics. Doing so will minimize costly mistakes and help managers better allocate their resources regarding use of their marketing tactics.

The article shows that targeted and non-targeted customers perceive the influence of marketing tactics differently. Among the five marketing tactics, the targeted or favored customers respond to the level of service quality, communication and customization more strongly. The non-targeted customers – those not favored or explicitly targeted by retailers – respond to the level of price and reputation more strongly. However, customization and reputation were not statistically significant. Further research of marketing tactics and customers in a different setting, such as in a high-involvement context, is thus warranted; such research would help marketers clarify which factors influence targeted and non-targeted customers in different contexts.

The findings suggest that distinguishing between targeted and non-targeted customers using varying customer feelings is a key factor to customer favoritism tactics. Examining this distinction of customers’ feelings associated with ‘advantaged’ (or guilt and satisfaction) – and ‘disadvantaged inequality’ (or anger) would enable managers to group their customers more effectively to identify which group needs more attention. Such identification and awareness of targeted and non-targeted customers would help marketers develop more appropriate approaches for tailoring offers to the customers whose perceptions may result in anger or outrage. That is, marketers would be able to take action and better control damage20 regarding any issues related to the two groups. Intuitively, targeted customers respond more strongly to service and communication because they already have a good relationship with their provider and thus are more engaged in a dialogue and less concerned about price; non-targeted customers do not have any relationship with their provider, and thus simply focus on prices.

For managers, a useful finding is the structured study of the customer profiles of the targeted and non-targeted customers, which enables firms to detect specific customers and their different perceptions. Managers should develop a system to manage their targeted and non-targeted customers according to their perceptual differences. In terms of implementation of a marketing strategy, managers can use their knowledge about the targeted and non-targeted customers as part of a more comprehensive segmentation scheme. Replication of this study's methodology and variables is warranted and would reveal such varying behaviors among a retailer's customers, regardless of whether they are students, as in the current study.

As mentioned previously, the two groups’ choices of preferred method for marketing communications were friends’ suggestions (word of mouth) on any form of offers and television advertisements. The findings show that marketers should beneficially develop marketing schemes around customers’ stated preferences.

In an increasingly customized environment, effective implementation of marketing tactics requires an understanding of the level of impact of each of the marketing tactics on different customer groups. This study shows that some marketing tactics exert more influence than others. In other words, different customers respond to different marketing tactics. This factor is due to the notion that targeted and non-targeted customers differ in their perceptions of the relative influence of marketing tactics and offerings. This study shows that marketers can undertake different efforts, such as considering differential treatment of customers, with certain marketing tactics.

This study offers actionable managerial guidance on specific marketing tactics and on how targeted and non-targeted customers can be managed in a retail setting. Specifically, the findings indicate that price, service quality and communication help enhance and maintain long-term relationships. Thus, the findings provide managers with the capability: (i) to identify and use an appropriate marketing tactic to maintain relationships by tailoring offerings that suit the targeted customers with service and communication and (ii) to enhance relationships by tailoring tactics to non-targeted customers with price.

In contrast to conventional target marketing practices, which often disregard non-targeted customers, this study shows that to create a successful strategy, marketers must manage both customer groups and understand the level of influence of the marketing tactics. This is a key contribution of this study. Future studies should address the limitations in this study related the contextual limitations and to the sample. The potential of conducting a large scale study of targeted and non-targeted echoes into many contexts such as ‘favored’ versus ‘non-favored’ consumers; ‘profitable’ versus ‘non-profitable’ customers; ‘gay’ versus ‘non-gay’ consumers; and ‘switchers’ versus ‘stayers’ and so on due to the use of basic feelings and emotions in the present study. The conceptualization of what constitutes targeted (or valued) and non-targeted (or non-valued) suggests that a firm may be able to define their own value sets and adapt the present framework into their specific context, in order to improve their understanding of how those two key groups of customers should be managed. The present study acknowledges that addressing both targeted and non-targeted customers is important and should not be neglected. For certain groups, other marketing tactics may be more important than in the current setting, and that in itself poses an interesting stream of research.

References

Simonson, I. (2005) Determinants of customers’ responses to customized offers: Conceptual framework and research propositions. Journal of Marketing 69 (1): 32–45.

Palmatier, R.W., Scheer, L.K., Evans, K.R. and Arnold, T.J. (2008) Achieving relationship marketing effectiveness in business-to-business exchanges. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 36 (2): 174–190.

Venkatesan, R. and Farris, P. (2012) Measuring and managing returns from retailer-customized coupon campaigns. Journal Of Marketing 76 (1): 76–94.

Boulding, W., Staelin, R., Ehret, M. and Johnston, W.J. (2005) A customer relationship management roadmap: What is known, potential pitfalls, and where to go. Journal of Marketing 69 (4): 155–166.

Dibb, S. and Simkin, L. (2009) Implementation rules to bridge the theory/practice divide in market segmentation. Journal of Marketing Management 25 (3–4): 375–396.

Lo, A.K.C., Lynch Jr, J.R. and Staelin, R. (2007) How to attract customers by giving them the short end of the stick. Journal of Marketing Research 44 (1): 128–141.

Rust, R.T., Lemon, K.N. and Zeithaml, V.A. (2004) Return on marketing: Using customer equity to focus marketing strategy. Journal of Marketing 68 (1): 109–127.

Nguyen, B. (2010) Understanding the Perceptual Differences between Targeted and Non-targeted Customers. APBITMS 2010 Conference, Beijing, China.

Reinartz, W., Krafft, M. and Hoyer, W.D. (2004) The customer relationship management process: Its measurements and impact on performance. Journal of Marketing Research 41 (3): 293–305.

Cao, Y. and Gruca, T.S. (2005) Reducing adverse selection through customer relationship management. Journal of Marketing 69 (4): 219–229.

Berry, L.L. (1995) Relationship marketing of services-growing interest: Emerging perspectives. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 23 (4): 236–245.

Bansal, H.S., Taylor, S.F. and Yannik St., J. (2005) Migrating to new service providers: Toward a unifying framework of consumers switching behaviors. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 33 (1): 96–115.

Peng, L.Y. and Wang, Q. (2006) Impact of relationship marketing tactics (RMTs) on switchers and stayers in a competitive service industry. Journal of Marketing Management 22 (1/2): 25–59.

Nguyen, B. and Simkin, L. (2009) An Examination of the Role of Fairness in CRM: A Conceptual Framework. Proceedings of the british academy of management 2009. Brighton, UK: University of Brighton.

De Wulf, K., Odekerken-Schröder, G. and Iacobucci, D. (2001) Investments in customer relationships: A cross-country and cross-industry exploration. Journal of Marketing 65 (4): 33–50.

Homans, G.C. (1961) Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World.

Huppertz, J.W., Arenson, S.J. and Evans, R.H. (1978) An application of equity theory to buyer-seller exchange situations. Journal of Marketing Research 15 (2): 250–260.

Adams, J.S. (1965) Inequity in social exchange. In: L. Berkowitz (ed.) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. New York: Academic Press, pp. 267–299.

Jacoby, J. (1976) Consumer research: Telling it like it is. In: B.B. Anderson (ed.) Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 3. Cincinnati, OH: Association for Consumer Research, pp. 1–11.

Xia, L., Monroe, K.B. and Cox, J.L. (2004) The price is unfair! A conceptual framework of price fairness perceptions. Journal of Marketing 68 (4): 1–15.

Major, B. and Testa, M. (1989) Social comparison processes and judgments of entitlement and satisfaction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 25 (2): 101–120.

Blodgett, J.G., Hill, D.J. and Tax, S.S. (1997) The effects of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice on postcomplaint behavior. Journal of Retailing 73 (2): 185–210.

Homburg, C., Hoyer, W.D. and Stock, R.M. (2007) How to get lost customers back. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 35 (4): 461–474.

Leventhal, G.S. (1980) What should be done with equity theory? In: K.J Gergen, M.S. Greenberg and R.H. Willis (eds.) Social Exchange: Advances in Theory and Research. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 27–55.

Kahneman, D. and Knetsch, J.L. (1986) Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking entitlements in the market. American Economic Review 76 (4): 728–741.

Campbell, M.C. (1999) Perceptions of price unfairness: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing Research 36 (2): 187–199.

Folkes, V.S. (1988) Recent attribution research in consumer behavior: A review and new directions. Journal of Consumer Research 14 (4): 548–565.

Maxwell, S. (1995) What makes a price increase seem ‘fair'? Pricing Strategy Practice 3 (4): 21–27.

Jewell, R.D. and Barone, M.J. (2007) Norm violations and the role of marketplace comparisons in positioning brands. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 35 (4): 550–559.

Urbany, J.E., Bearden, W.O. and Weilbaker, D.C. (1988) The effect of plausible and exaggerated reference prices consumer perceptions and price search. Journal of Consumer Research 15 (1): 95–110.

Bougie, R., Pieters, R. and Zeelenberg, M. (2003) Angry customers don’t come back, they get back: The experiences and behavioral implications of anger and dissatisfaction in services. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 31 (4): 377–393.

Zeelenberg, M. and Pieters, R. (2004) Beyond valence in customer dissatisfaction: A review and new findings on behavioral responses to regret and disappointment in failed services. Journal of Business Research 57 (4): 445–455.

Sinha, I. and Batra, R. (1999) The effect of consumer price consciousness on private label purchase. International Journal of Research in Marketing 16 (3): 237–251.

Helson, H. (1948) Adaptation-level as a basis for a quantitative theory of frames of reference. Psychological Review 55 (6): 297–313.

Jayachandran, S., Sharma, S., Kaufman, P. and Raman, P. (2005) The role of relational information processes and technology use in customer relationship management. Journal of Marketing 69 (4): 177–192.

Thomas, J.S. and Sullivan, U.Y. (2005) Managing marketing communications with multi-channel customers. Journal of Marketing 69 (4): 239–251.

Woodside, A.G. and Walser, M.G. (2006) Building strong brands in retailing. Journal of Business Research 60 (4): 1–10.

Sahlins, M. (1972) Stone Age Economics. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

Sin, L.Y.M., Tse, A.C.B. and Yim, F.H.K. (2005) CRM: Conceptualization and scale development. European Journal of Marketing 39 (11/12): 1264–1290.

Payne, A. and Frow, P. (2005) A strategic framework for customer relationship management. Journal of Marketing 69 (4): 167–176.

Keaveney, S.M. (1995) Customer switching behavior in service industries: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing 59 (2): 71–82.

Grönroos, C. (1996) Relationship marketing logic. Asia-Australia Marketing Journal 4 (1): 7–18.

Gummesson, E. (1999) Total Relationship Marketing. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Lichtenstein, D.R., Ridgway, N.M. and Netemeyer, R.G. (1993) Price perceptions and consumer shopping behaviour: A field study. Journal of Marketing Research 30 (2): 234–245.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. and Berry, L.L. (1988) SERVQUAL: A multiple item scale for measuring consumers’ perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing 64 (1): 12–40.

Spreng, R.A. and MacKoy, R.D. (1996) An empirical examination of a model of perceived service quality and satisfaction. Journal of Retailing 72 (2): 201–214.

Bart, Y., Shankar, V., Sultan, F. and Urban, G.L. (2005) Are the drivers and role of online trust the same for all web sites and consumers? A large-scale exploratory empirical study. Journal of Marketing 69 (4): 133–152.

Fombrun, C.J., Gardberg, N.A. and Sever, J.M. (2000) The reputation quotient: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. Journal of Brand Management 4 (4): 241–255.

Fornell, C., Johnson, M.D., Anderson, E.W., Cha, J. and Bryant, B.E. (1996) The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of Marketing 60 (4): 7–18.

Luyten, P., Fontaine, J.R.J. and Corveleyn, J. (2002) Does the test of self-conscious affect (TOSCA) measure maladaptive aspects of guilt and adaptive aspects of shame? An empirical investigation. Personality and Individual Differences 33 (8): 1373–1387.

Campbell, M.C. (2007) Says who?! How the source of price information and affect influence perceived price (un)fairness. Journal of Marketing Research 44 (2): 261–271.

Finkel, N.J. (2001) Not Fair! The Typology of Commonsense Unfairness. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Lee-Wingate, S.N. and Stern, B.B. (2006) Perceived fairness: Conceptual framework and scale development. Advances in Consumer Behavior 34: 400–402.

Kumar, N., Scheer, L. and Steenkamp, J.B. (1998) Interdependence, punitive capability, and the reciprocation of punitive actions in channel relationships. Journal of Marketing Research 35 (2): 225–235.

Hair, J.F., Black, B., Babin, B., Anderson, R.E. and Tatham, R.L. (2006) Multivariate Data Analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, B., Li, M. & Chen, CH. The targeted and non-targeted framework: Differential impact of marketing tactics on customer perceptions. J Target Meas Anal Mark 20, 96–108 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2012.7

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2012.7