Abstract

Knowledge sharing and learning are critically important to the success of knowledge management. In this research, we study the design of incentive rewards to facilitate knowledge transfer utilizing an internal knowledge market within organizations. The internal knowledge market is modelled as a marketplace where knowledge providers can send signals about their knowledge and learners may voluntarily acquire the knowledge based on the signals. Three types of knowledge recipients are differentiated with respect to their signalling threshold functions: knowledge connoisseur, knowledge public, and knowledge dilettante. In addition, a knowledge recipient may be either humble or arrogant, with different propensities for learning characterized by different learning inhibition cost functions. For different knowledge recipients, we study the knowledge providers’ best signalling strategies and the firm's optimal design of reward structures. Knowledge providers will adopt different signalling strategies if they lack the necessary trust that knowledge recipients will accurately report their learning. We analyse how the firm can offer learning rewards and employ IT support to improve the trust so as to increase knowledge transfer. This research provides valuable insights for practitioners to manage an internal knowledge market.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Athreye SS (1997) On markets in knowledge. Journal of Management & Governance 1 (2), 231–254.

Ba S, Stallaert J and Whinston AB (2001) Optimal investment in knowledge within a firm using a market mechanism. Management Science 47 (9), 225–239.

Bakos Y (1997) Reducing buyer search costs: implications for electronic marketplaces. Management Science 43 (12), 1676–1692.

Bakos Y (1998) The emerging role of electronic marketplaces on the Internet. Communications of the ACM 41 (8), 35–42.

Brydon M and Vining AR (2006) Understanding the failure of internal knowledge markets: a framework for diagnosis and improvement. Information and Management 43 (8), 964–974.

Davenport HT and Prusak L (1998) Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Dennis AR and Vessey I (2005) Three knowledge management strategies: knowledge hierarchies, knowledge markets, and knowledge communities. MIS Quarterly Executive 4 (4), 399–412.

Desouza K, Awazu Y, Yamakawa S and Umezawa M (2005) Facilitating knowledge management through market mechanism. Knowledge and Process Management 12 (2), 99–107.

Desouza KC and Awazu Y (2003) Constructing internal knowledge markets: considerations from mini cases. International Journal of Information Management 23 (4), 345–353.

Eames D, Baer F, Mulligan D and Jirele T (2001) Best Buy's knowledge management journey. [WWW document] http://www.apqc.org/knowledge-base/documents/best-buys-knowledge-management-journey (accessed 28 September 2010).

Eschenfelder K, Heckman R and Sawyer S (1998) The distribution of computing: the knowledge markets of distributed technical support specialists. Information Technology & People 11 (2), 84–103.

Fang SC and Su HY (2008) Organizational knowledge creation: a knowledge market efficiency perspective. International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies 2 (2), 214–235.

Gale SF (2002) Knowledge-sharing earns bonus points. Workforce, HR Trends and Tools for Business Results [WWW document] http://www.workforce.com/section/benefits-compensation/archive/feature/knowledge-sharing-earns-bonus-points/233574.html (accessed 28 September 2010).

Guilhon B (2004) Markets for knowledge: problems, scope, and economic implications. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 13 (2), 165–181.

Hansen MT and Haas MR (2001) Competing for attention in knowledge markets: electronic document dissemination in a management consulting company. Administrative Science Quarterly 46 (1), 1–28.

Hansen TM, Nohria N and Tierney T (1999) What's your strategy for managing knowledge? Harvard Business Review 77 (2), 106–116.

Huysman M and Wulf V (2006) IT to support knowledge sharing in communities: towards a social capital analysis. Journal of Information Technology 21 (1), 40–51.

Kafentzis K, Mentzas G, Apostolou D and Georgolios P (2004) Knowledge marketplaces: strategic issues and business models. Journal of Knowledge Management 8 (1), 130–146.

Kamoon (2002) Securing the power of enterprise expertise: Kamoon's EEM matches the tough questions to the correct people. KMWorld, 1 May.

Lee HG and Clark TH (1996) Impacts of the electronic marketplace on transaction cost and market structure. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 1 (1), 127–149.

Matson E, Patiath P and Shavers T (2003) Stimulating knowledge sharing: strengthening your organization's internal knowledge market. Organizational Dynamics 32 (3), 275–285.

McAfee RP and McMillan J (1991) Optimal contracts for teams. International Economics Review 32 (3), 561–577.

McKinsey & Co (2004) Making a market in knowledge. The McKinsey Quarterly [WWW document] http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/3015575 (accessed 28 September 2010).

Michailova S and Husted K (2001) Dealing with knowledge sharing hostility: insights from six case studies. MPP Working Paper No. 10/2001, Department of Management, Politics and Philosophy, Copenhagen Business School.

Müller RM, Spiliopoulou M and Lenz HJ (2002) Electronic marketplaces of knowledge: characteristics and sharing of knowledge assets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Infrastructure for e-Business, e-Education, e-Science, and e-Medicine on the Internet (SSGRR 2002w (REISS ROMOLI, SSG Eds), L’Aquila, Italy.

Spence M (1973) Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 87 (3), 355–374.

Sundaresan S and Zhang Z (2004) Facilitating knowledge transfer in organizations through incentive alignment and IT investment. Vol. 8, Proceedings of the 37th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’04) – Track 8, pp 80249b, IEEE Computer Society, Washington DC.

Szulanski G (1996) Exploring internal stickiness: impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strategic Management Journal 17, 27–43.

Thomas J (2007) Enterprise knowledge market. [WWW document] http://mike2.openmethodology.org/wiki/Enterprise_Knowledge_Market (accessed 28 September 2010).

Vygotsky L (1978) Mind and Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Proof of Lemma 1: The first-order condition of worker i's surplus shows that

which indicates that the optimal signal strength s i * increases in k i but decreases in k j because μ(k j ) decreases in k j and ∂2 c i /∂s i ∂k i <0. □

Appendix B

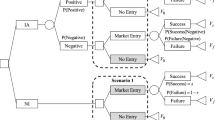

Proof of Lemma 2: s i * has to be in the range between two signal threshold functions α(k j ) and β(k j ). Otherwise, worker i will take different actions for signalling s i , either sending no signal or sending the signal at the expiring threshold function β(k j ), that is,

If the best signal s i * is so weak that it is less than the active threshold function α(k j ), worker j will not have enough interest to learn k i . Thus, worker i should not send any signals. If the best signal s i * is so strong that is greater than the expiring threshold function β(k j ), worker j will not learn k j because she has obtained enough knowledge from the signal. Therefore, worker i should decrease the signal strength to β(k j ). However, for the actual signal to stay at β(k j ) when s i *>β(k j ), the net benefit for signalling has to be positive, which requires the sufficient condition β(k j )⩾s̃ i (k i , k j ). This condition will be satisfied if k j β<k˜ j β, or if the intersection A between curves s i * and s̃ i is below the curve β(k j ), as demonstrated in Figure B1, that is, β(k̂ j )⩾s i *(k i , k̂ j )=s̃ i (k i , k̂ j ). From Figure 2,

Therefore, if the following condition holds,

worker i will always send β(k j ) when s i *>β(k j ).

To explore the effect of active threshold α(k j ), we compare the threshold knowledge level k j α, where s i *(k i , k j α)=α(k j α), with k̂ j . Eq. (B.1) indicates that s̃ i is always greater than α(k j ). Therefore, k̂ j is always less than k j α, which implies that worker i will not signal even for some s i * that is greater than the active threshold level α(k j ).

In summary, if the condition in Eq. (B.2) holds, worker j will have a strategy of sending her signal s i as summarized in Eq. (3). □

Appendix C

Proof of Proposition 1: Given the expected probability  of knowledge k

j

to be learned from worker i's signalling strategy (Eq. (4)), the firm maximizes its expected payoff

of knowledge k

j

to be learned from worker i's signalling strategy (Eq. (4)), the firm maximizes its expected payoff

by choosing a best sharing reward r s . □

Appendix D

Proof of Proposition 2: Worker i's individual-rationality constraint indicates that

for which the Envelope theorem suggests that,

which implies that the individual-rationality constraints can be reduced into

Since when worker i's knowledge k i =0, her payoff π i =w i , therefore, the firm should offer the participation reward as w i =U 0.

Alternatively, the firm's expected profit can be rewritten as

Therefore, the firm maximizes π by choosing the optimal r s . □

Appendix E

Design of sharing reward for arrogant recipients: five cases

Here are five possible cases for an individual provider's expected payoff.

Case I: When 0⩽k j l<k j βV, where k j βV is the expiring threshold knowledge level determined by s i V, an individual provider's expected payoff is

in which s i V is the modified signal strength based on the belief q 2 by

Case II: When k j βV⩽k j l<k j β, an individual provider's expected payoff is

Case III: When k j β⩽k j l<k̂ j V, as shown in Figure 9a, an individual provider's expected payoff is

where s i * is still the same as that with complete trust.

Case IV: When k̂ j V⩽k j l<k̂ j , an individual provider's expected payoff is

Case V: When k j l⩾k̂ j , an individual provider's expected payoff is

Since worker i's knowledge level is not observable, the firm can only maximize its expected payoff based on these five cases, that is, the firm's decision problem is now formulated as

in which k̂ i , k̂ i V, k i β, k i βV are worker i's threshold knowledge levels where k̂ j (k̂ i )=k̂ j V(k̂ i V)=k j β(k i β)=k j βV(k i βV)=k j l=L −1(r l ).

Appendix F

Design of sharing reward for humble recipients: five cases

Here are five possible cases for an individual provider's expected payoff.

Case I: When 0⩽k j l<k j βV, an individual provider's expected payoff is

Case II: When k j βV⩽k j l<k j β, an individual provider's expected payoff is

Case III: When k j β⩽k j l<k̂ j V, as shown in Figure 9b, an individual provider's expected payoff is

Case IV: When k j V⩽k j l<k̂ j , an individual provider's expected payoff is

Case V: When k j l⩾k̂ j , an individual provider's expected payoff is

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Sundaresan, S. Knowledge markets in firms: knowledge sharing with trust and signalling. Knowl Manage Res Pract 8, 322–339 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2010.22

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2010.22