Abstract

Governments of many Western countries are committed to render the pension system sustainable in the long term. We study the links between pension reforms, retirement age, income and retirement decisions by examining data from two nationwide surveys in Italy and the UK. While the Italian system remains centred on state pension, the UK places greater emphasis on private savings and on the increase of retirement age. Our analysis of the differences in retirement decisions between the UK and Italy over a ten-year period (1992–2002) allows us to determine the effective retirement ages and reveal a greater volatility in the average Italian retirement age compared to the UK. By investigating the relationship between income and retirement age, we conclude that, in both countries, high earners retire relatively early, while those in the lowest income groups tend to retire later; however, there are marked differences in the way our two samples behave over the period studied.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, governments of all political persuasion have shown a commitment towards sustainable pension systems with the introduction of incentives and through encouraging saving for retirement. Many developed countries have had to make adjustments to render pay-as-you-go pension systems sustainable, set against the trend of early retirement or withdrawal from the labour markets of the 1980s and 1990s. Although this trend is starting to reverse, it has stimulated a debate on the reform of funded and unfunded pension schemes, the age of retirement and the adequacy of post-retirement income. The debate on pension policy is now focused heavily on the determinants of pre- and post-retirement income and age of retirement. A number of studies in the UK, USA and to a lesser extent in Italy have investigated the link between income and retirement age1, 2 as well as its adequacy after retirement.3, 4, 5, 6 What we seek to address, however, is the relationship between income replacement ratios and retirement age for different income groups and different countries. This research allows us to compare differences between the UK and Italy, and in particular highlight the way in which the Italian pension system puts less responsibility on the individual compared to the UK.

Previous work in this area links retirement decisions, particularly early retirement, to private pension provision and the incentives associated with it and to the generosity of the Social Security System.5, 6, 7, 8 Consecutive reforms in the UK, however, have led to a reverse in the retirement age trend. While Blundell et al.5 find that incentives offered by occupational pension schemes are likely to encourage early retirement, Gough and Arkani9 illustrate that since 1999 the trend of the average age of retirement has started to revert. Following the European Employment Directive, the UK government has recently introduced new legislation, which prevents age discrimination in employment, in the hope of prolonging the retirement ages of employees.10 According to current legislation, employers’ mandatory retirement ages, if lower than 65, can be considered age discrimination unless justifiable.11 Since 1992 governments in Italy have also been concentrating their efforts on keeping people in employment for longer, through a series of reforms. Until the mid-1990s, however, about 40 per cent of those employed were still allowed to retire at the more favourable pre-1992 conditions, creating new temporary incentives to early retirement, with a view to impending tighter retirement conditions.12

Using data on Italian and British individuals over the ten years, between 1992 and 2002, we examine the trends of retirement age and pre- and post-retirement income. Previous research indicates that income post-retirement is an important determinant of the retirement decision, which can be explained by the saving implication of the lifecycle model.6, 13, 14 The lifecycle framework contends that agents make successive decisions to achieve financial stability using available information in the most efficient way possible.15 One of the primary implications of pension saving is that households try to allocate consumption expenditure to maintain their marginal utility of wealth as constant over time. In his paper on the analysis and recommendations of the UK Pension Commission, Hills16 maintains, however, that people’s saving behaviour in particular is affected by inertia and does not necessarily follow a trend that would optimise utility.

In this paper, we also address the issue of retirement funding and its impact on both retirement age and income post-retirement. In the past, retirement funding policies in Italy have differed significantly from those adopted in the UK; however, in the last ten years policy makers seem to have embraced converging views that the private sector ought to play a bigger role in pension provision. Despite the ratification of three pension reforms since 1992, aimed at prolonging employees’ working life and reducing the burden of state pension provision, pension expenditure in Italy has continued to grow, reaching 14.9 per cent of the GDP in 2002, while the respective figure for the UK was 11.7 per cent.17 The basic state pension typically represents the major source of income post-retirement in the Italian pension system. Attanasio and Brugiavini18 in their study on the effects of social security policies on household savings find that public pension wealth is a substitute for private saving, which explains the consistent downward trend of saving rates among Italian households, since the mid-1980s.19 In the UK, on the other hand, saving rate trends have experienced a high volatility. Sharp rises in saving rates due to cyclical adjustments, the recessions of the late 1970s and early 1990s, and the pension reforms of the last two decades19, 20 were followed by periods of falling saving rates associated with high consumer confidence in the mid-1980s and more recently, since 1998.20 Baldini et al.21 and Attanasio and Brugiavini18 observe that in Italy, the enactment of three pension reforms between 1992 and 1997 have not yet significantly stimulated the low saving rate of Italian households.

The aim of this paper is to contribute to the debate on retirement age and retirement decisions based on pre- and post-retirement incomes by examining two nationwide samples from the UK and Italy. The paper is structured as follows. In the next section we explore the changes in the average actual retirement age between the two countries and in the subsequent section we examine the age of retirement by income drawing differences and similarities between Italy and the UK. The penultimate section examines the relationship between income replacement ratios and retirement age and shows how replacement rates have changed across time, and finally in the last section we draw our conclusions.

Retirement age in the UK and Italy

Understanding retirement age is a complex issue partly due to the way retirement is defined and in part due to its dependence on a number of factors. Retirement choices depend on health, financial and domestic circumstances, work satisfaction of employees on the one hand, and the discretion of managers and pension funds, or changes in the labour market, on the other.22, 23, 24 Much research links retirement decisions, particularly early retirement, to private pension provision and their incentives.3, 5, 6, 7

When trying to calculate the retirement age, UK research to date has mainly relied on data from the Retirement Surveys of 1988–1989 and 1994, although more recently researchers have started drawing on the data from the English Longitudinal Survey of Ageing.25 Banks and Blundell,7 Blake6 and Blundell et al.5 have all used econometric models to project retirement age. The problem, however, with econometric models of older people’s labour market participation is that their speculative nature is based on simulation. Two key problems exist with the above approaches to estimating retirement age: first, retirement does not necessarily follow exit from the labour market as people may leave the labour market due to ill health, voluntary or involuntary redundancy, or choice of lifestyle,26, 27, 28, 29 and secondly probabilistic models are merely simulations of reality; they do not represent reality. In order to obtain a more accurate picture of the actual retirement ages, criteria are needed to define retirement and construct a method for measuring it.

For this purpose, we draw on the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS),30 which comprises an annual survey of households throughout the UK. At its inception in 1991, 5,000 households were interviewed, and since then the survey has grown to include around 9,000 households in order to increase the accuracy of its national representation. Individuals from ages 11 upwards are interviewed in each household and detailed financial, occupational and lifestyle data are collected. We selected BHPS over other national household surveys because of its reasonable length of historical development and longitudinal approach, which allows us to assess the pre- and post-retirement incomes of individuals, without requiring us to statistically approximate these quantities from groups of similar but distinct households. The Italian data we used were collected from the Survey of Household Income and Wealth carried out by the Bank of Italy.31 This is published bi-annually and comprises a sample of about 8,000 households, including over 20,000 individuals across 300 municipalities, interviewed every two years. The survey provides an in-depth examination of demographic, social and economic information, which includes data on incomes (sources and amounts, both at individual and household levels), savings and expenditures.

The retirement age for both countries is calculated by looking at the reported employment status of the respondent, between the years 1992 and 2002. If in a considered year, the respondent is recorded as retired but in the previous year was not recorded as retired, then the considered year is given as the year of retirement and the respondent’s age at the interview date is given as the age of retirement. The employment status of the respondent is self-identified, through their responses to the question that states ‘Please look at this card and tell me which best describes your current situation?’ The possible responses are ‘in paid employment’, ‘self-employed’, ‘not employed’. If ‘not employed’ the respondent must then proceed to define his/her status as ‘looking for first employment’, ‘housewife’, ‘unemployed’, ‘job pensioner’, ‘long-term sick or disabled’, ‘in the military service’ or ‘other’, which are found under the ‘not employed’ header. The same method of analysis is employed for the Italian data. The results from the computations of the average retirement age in the UK and Italy between 1992 and 2002 are shown in Figure 1.

The dissimilarities in the retirement age within the UK and Italy can be attributed to many factors, for instance changes in schemes as pension rights can take many years to accumulate. The UK sample is more stable and shows higher values of retirement age for the whole period analysed, as many companies have removed the generous early retirement incentives within the defined benefits schemes. Falling annuity rates also discouraged members in defined contribution schemes from taking early retirement.7 Secondly, the normal retirement age (NRA) of private sectors schemes rose between 1987 and 2000; the number of active members in private pension schemes with an NRA of 60 declined while members in schemes with an NRA of between 60 and 65 increased.32

The Italian sample, on the other hand, appears more volatile for several reasons. First, unlike in the UK, workers can achieve a seniority (long service) pension, which entitles them to a state pension after a minimum contributory period, regardless of their age.33 Secondly, the 1992 reform and its subsequent amendments in 1995 and 1998 determined an increase in the age of retirement in the private sector from 55 to 60 for women and from 60 to 65 for men, which also helps to explain the clear overall increase of average retirement age from 56 in 1992 to above 60 in 2002. Thirdly, in the period considered, there is a noticeable difference between private and public sector workers. In 1992, the minimum number of years of contribution entitling public sector workers to a seniority pension was raised by over ten years, from 15 to 20 and later gradually raised to 35; a requirement already in effect for private sector workers.34 Fourthly, in an attempt to reduce unemployment, the existence of incentives provided by the Italian Social Security system to supply labour under the form of an early retirement provision, without actuarial penalty, distorts choices in favour of early retirement.8

Blöndhal and Scarpetta35 calculated the average retirement age for the UK over a period of 45 years based on Kaplan–Meier estimators from Labour Force Survey (LFS) data,10, 29 while Gough and Arkani9 use actual retirement ages for the period 1984–2003 by defining retirement and measuring it by observing the respondent’s economic activity as expressed in the LFS and Quarterly Labour Force Survey data sets. Both studies indicate a stable trend after 1992 and Gough and Arkani’s calculations show a slight decline of retirement age after 1998. Our results coincide with Blöndhal and Scarpetta’s estimates up to 1995, and with Gough and Arkani’s data up to 1998, although between 1999 and 2002 our average trend deviates from Gough and Arkani’s by about a year. This difference can be attributed to the different data sets used in the two studies since our data are measured by looking at the reported employment status of the respondent each year, whereby to be classified as retired respondents must have left their main job. Gough and Arkani,9 on the other hand, define retirement within a particular year as the withdrawal from the labour market in the preceding 12 months combined with retirement from economic activity.

Brugiavini and Peracchi36 analyse the retirement decisions of Italian workers in the private sector for a period of 20 years following policy changes. They model the workers’ decisions by using incentive measures as well as sex and age as predictors and find an increase of the mean retirement age in response to policy changes. Contini and Fornero37 find that cohorts involved in the pension transitions of the 1990s show an effect in terms of increase in retirement age, while Franco38 states that the lengthy Italian reform process generates uncertainty and limits the benefit of the actuarial approach introduced by the 1995 reform, which links wage replacement to retirement age, and encourages workers to retire as soon as they can for fear of possible cuts in pension benefits. This uncertainty on pension benefits helps explain the volatility of our data, which, however, shows a definite upward trend in retirement age as consequence of the reforms that took place from 1992 reaching a peak of 60.2 in 2000, and in 2002. These results coincide with findings of Brugiavini and Peracchi,36 who analysed Italian planned retirement age between 1989 and 2000 and found that employees affected by the reforms of the 1990s plan overall to retire 11 months later (from 60.2 to 61.1 years of age) compared to those not affected by them.

Retirement age by income

There is general consensus among academics about pension benefits and retirement age and, to a lesser extent, about the relationship between saving and retirement age,20, 39, 40 but little can be found on income pre- and post-retirement and its links with retirement decisions. Meghir and Whitehouse2 found that increased earnings in work may delay retirement, implying that economic incentives are determinants to retirement age. In his analysis of the impact of state and private pension wealth on retirement decisions, Blake6 found that wealth from different types of pension schemes produce different outcomes in the retirement age. He also concludes that wealth from state pensions appear to have no effect on the retirement decision. Important work on retirement decisions in the US, conducted by Mitchell and Fields,1 analysed retirement behaviour using a sub-sample of the Benefit Amount Survey by the US Department of Labor. They found that ‘differences in income at older ages significantly influenced retirement patterns’, as a consequence individuals with a higher income at 60 retired earlier; however, they also postponed retirement if they were likely to gain more by working longer.

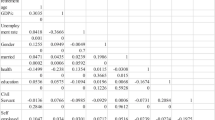

In both the BHPS and the Bank of Italy data sets, figures on income are defined as the sum of labour and nonlabour incomes. Nonlabour income sources are pensions, benefits, transfers and income from investment. Thus, the incomes of respondents retiring between 1992 and 2002 are assessed before and after they retire, with groups formed by income quantile. The relations between retiree age, retirement year and income quantile are analysed. We examine detailed information on pre- and post-retirement incomes for individuals of the same panel over ten years, starting from 1992, and analyse income levels of heads and nonheads of households around the time of retirement. To account for inflation and change in purchasing power over the years, households were split into three pre-retirement income quantiles. For each year the bottom 33 per cent (lowest incomes) was always allocated to quantile 1, the next 33 per cent allocated to quantile 2 and the top 33 per cent (highest incomes) allocated to quantile 3. Individuals retire at different ages, and Figures 2 and 3 present the actual retirement ages for each quantile, between 1992 and 2002.

The two graphs on retirement age by income quantile between 1992 and 2002 present some similarities. In both countries, employees belonging to the bottom quantile retire later (at 61.5 in 2002 in Italy, at 63.1 in the UK), while the higher age of retirement for UK workers across all quantiles is consistent with our previous results on average retirement age. Individuals in the top income quantile show a tendency to retire earliest in both countries, although in the UK the trend is far more evident. These results concur with Mitchell and Fields’1 findings on the relationship between pre-retirement income and age of retirement. The main discrepancy between our two data sets is represented by the behaviour of those belonging to the middle-income quantile. In the UK, their behaviour appears to be more in line with those in the lowest income group, while in Italy their retirement decision is more in line with that of the highest income quantile.

Income replacement ratios by year and age

Replacement ratios have been used for a number of years to measure the extent to which state benefits are to be considered work disincentives8, 41 and to compare social systems’ generosity around the world.42, 43, 44 Herbertsson45 suggests that systems with high replacement ratios prompt workers to retire earlier, as was proven by Johnson46 in his study on labour force participation of 13 industrialised countries. Johnson found negative participation elasticity to post-retirement wealth for male workers aged 60–64. Other studies, however, have failed to confirm the relationship between high replacement rates and early retirement.35 In an attempt to measure the level of state benefits for Italian retiring employees, Brugiavini and Peracchi8 recently examined income replacement rates, defined as ratios between pension benefits at retirement and pensionable earnings. They analysed the effect of social security wealth on retirement decisions of private sector nonagricultural employees over a 20-year period from 1977 to 1997. Using microeconomic data from the Italian National Social Security Institute to predict retirement rates under alternative social security regimes (the Amato regime, the Dini/Prodi reform, an actuarial adjustment case), they showed that lower levels of state benefits have greater effects on retirement decisions among people choosing to prolong their working life. Cremer and Pestieau47 argue that UK replacement rates are significantly lower than the Italian rates and that the difference between ratios grows with the increase of income.

We define pension replacement ratios as the level of total income post-retirement divided by the total income pre-retirement, where both income pre- and post-retirement include nonlabour income sources such as pensions, benefits, transfers and income from investment. We examine the incomes of household members who retired during the 1992–2002 period, both before and after retirement to calculate income replacement ratios. For those who retired during the period we calculate the replacement ratios according to pre-retirement incomes quantiles. Figures 4 and 5 display the replacement ratios by year and income for Italy and the UK, while Figure 6 shows the aggregate trend in replacement ratios for the two countries over the ten-year period analysed.

Our analysis of replacement ratios by income quantiles reveals a number of interesting findings. First, the graph representing the average replacement ratios over all income quantiles across time shows that in the UK they range from a minimum of 76 per cent in 1993 to a maximum of 94 per cent in 1999. The data show a slight upward trend over the period examined, determined primarily by the increasing values for the lowest income quantile. The same graph also exhibits a difference between UK and Italian replacement ratios that reached a maximum of nearly 22 per cent in 1993, as the Italian ratios are constantly higher over the ten-year period. The data in Figure 6 also, however, indicate that a convergence of the replacement ratios seems to be taking place. The relatively low levels of income replacement rates in the UK were shown by Blundell et al.5 in their study on the effects of pension incentives on early retirement, and by Cremer and Pestieau47 in their analysis of European pension systems. Secondly, both in Italy and in the UK, those belonging to the lowest income quantile present the highest replacement rates for the entire ten-year period; this trend, however, is more evident for the UK sample, as confirmed by Cremer and Pestieau.47 Thirdly, we find that in Italy as well as in the UK, individuals in the top income quantile exhibit the lowest replacement ratios. Once again this trend emerges as more unequivocal for the UK, where individuals in the top two income quantiles show remarkably lower replacement ratios than those in the bottom quantile, while the data for Italy exhibit a higher concentration around the ‘all quantiles’ average.

Conclusion

In this paper, we present a comparative analysis of two national surveys with regard to retirement decisions, according to age and income pre- and post-retirement in Italy and the UK. Different political choices on pension provision in Italy and the UK have greatly influenced both retirement age and post-retirement income.

Our paper reveals that over the income groupings and time period examined, the UK average retirement age is higher and more stable than the Italian one. This trend highlights that in the UK retirement age experienced an increase from 1993 to 1999 followed by a slight decrease between 1999 and 2002, while overall it has declined from 62.4 to 61.8 over the period studied. In Italy, employees have consistently been postponing their retirement since 1992 with an average retirement age of just over 60.2 in 2002 compared to an average age of 55.9 in 1992. Our results for the UK are supported by those of Blöndhal and Scarpetta35 and Gough and Arkani,9 while our findings on the Italian sample correspond with other previous studies.36 Franco38 states that the high levels of volatility detected within the Italian retirement age trend link the lengthy Italian reform process to the uncertainty surrounding pension benefits. Our data reveal that the retirement age trends for the two countries have been converging in the decade between 1992 and 2002, with a clear upward trend for Italy, in agreement with policy objectives.

The relationship between retirement age and income suggests that in both countries employees in the lowest income group retire later than wealthier employees, and those at the top of the salary scale tend to retire the earliest. This trend, however, is more pronounced in the UK than in Italy. While in Italy employees in the middle-income group show a more similar behaviour to their wealthier counterparts, in the UK those belonging to the middle-income quantile exhibit a trend closer to those in the lowest income group. This builds on Blundell et al.’s finding that there is a significant wealth effects on retirement decisions, and adds to a number of previous studies that focused on the link between pre-retirement income and retirement age in USA and the UK.1, 2, 6

The analysis of replacement ratios shows higher rates for those in the lowest income groups, evidence supported by Blundell et al.5 and by Cremer and Pestieau47 for the UK; however, we are able to show that a similar trend also exists in Italy. In both countries those in the highest income groups have the lowest replacement rates. This appears more evident for the UK, where replacement ratios range from a minimum of 76 per cent in 1993 to a maximum of 94 per cent in 1999, and show an upward trend over the period examined. In Italy replacement ratios are consistently higher than in the UK across all income groups; however, the gap between the two countries was wider between 1993 and 1996, while they show more converging trends in the late 1990s and in 2000. Finally, we find that both in Italy and in the UK individuals in the top income group consistently exhibit the lowest replacement ratios; however, while this is more evident in the UK, the Italian data appear more concentrated around the average.

This paper has shown the convergence of retirement age levels and post-retirement income replacement ratios between Italy and the UK over the last ten years; this can be attributed to many changes, for example changes recently undertaken in pension policies by the respective governments. Our data indicate that, although the policies put in place in the two countries to achieve pension sustainability remain different in essence, with the UK focusing more on individual responsibility, while the Italian system is still centred around state pension, although to a lesser extent than in the past, a convergence of key indicators such as pension age and income replacement is taking place. The succession of pension reforms introduced by Italian governments since 1992 is forcing people into considering alternatives to state pension provision and into prolonging their working life. Although income replacement ratios in the UK are still over 20 per cent lower than in Italy, the average national trends suggest that in both countries employees may be taking actions in the years preceding retirement, by incrementing their savings to boost their declining post-retirement state income provisions.

References

Mitchell, O. S. and Fields, G. S. (1984) ‘The economics of retirement behavior’, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 84–105.

Meghir, C. and Whitehouse, E. (1997) ‘Labour market transitions and retirement of men in the UK’, Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 79, No. 2, pp. 327–354.

Tanner, S. (1998) ‘The dynamics of male retirement behaviour’, Fiscal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 175–196.

Banks, J., Blundell, R., Disney, R. and Emmerson, C. (2002) ‘Retirement, pensions and the adequacy of saving: A guide to the debate. www.ifs.org.uk.

Blundell, R., Meghir, C. and Smith, S. (2002) ‘Pension incentives and the pattern of early retirement’, The Economic Journal, Vol. 112, No. 478, pp. 153–170.

Blake, D. (2004) ‘The impact of wealth on consumption and retirement behaviour in the UK’, Applied Financial Economics, Vol. 14, No. 8, pp. 555–576.

Banks, J. and Blundell, R. (2005) ‘Private pension arrangements and retirement in Britain’, Fiscal Studies, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 35–53.

Brugiavini, A. and Peracchi, F. (2003) ‘Social security wealth and retirement decisions in Italy’, Labour — Review of Labour Economics and Industrial Relations, Vol. 17 (Special Issue), pp. 79–114.

Gough, O. and Arkani, S. (2007) ‘The impact of occupational pensions on retirement age’, Journal of Social Policy, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 297–318.

The Pensions Commission (2005) ‘A New Pension Settlement for the Twenty-First Century’, Second report of the Pensions Commission. The Stationary Office, www.pensionscommission.org.uk.

Department of Trade and Industry (2005) ‘Partial regulatory impact assessment’, Employment Relations Directorate, http://www.berr.gov.uk/.

Franco, D. (2000) ‘Italy: A never-ending pension reform’, in Feldstein, M. and Siebert, H. (eds.) ‘Social Security Pension Reform in Europe’, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Crawford, V. P. and Lilien, D. M. (1981) ‘Social security and the retirement decision’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 96, No. 3, pp. 505–529.

Zweimüller, J. (1993) ‘Partial retirement and the earnings test’, Journal of Economics, Vol. 57, No. 3, pp. 295–303.

Browning, M. and Crossley, T. F. (2001) ‘The life-cycle model of consumption and saving’, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 3–22.

Hills, J. (2006) ‘A new pension settlement for the twenty-first century? The UK Pension commission’s analysis and proposals’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 113–132.

Broese van Groenou, M., Glaser, K., Tomassini, C. and Jacobs, T. (2006) ‘Socio-economic status differences in older people's use of informal and formal help: A comparison of four European countries’, Ageing and Society, Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 745–766.

Attanasio, O. P. and Brugiavini, A. (2003) ‘Social security and households’ saving’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118, No. 3, pp. 1075–1119.

De Serres, A. and Pelgrin, F. (2003) ‘The decline in private saving rates in the 1990s in OECD Countries: How much can be explained by non-wealth factors?’, OECD Economic Studies, No. 36.

Disney, R., Emmerson, C. and Wakefield, M. (2001) ‘Pension reform and saving in Britain’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 70–94.

Baldini, M., Mazzaferro, C. and Onofri, P. (2002) ‘The reform of the Italian pension system, and its effects on saving behavior’, Fourth International Forum of the Collaborating Projects on Ageing Issues, Tokyo, Japan.

Guillemard, A. M. (1997) ‘Re-writing social policy and changes within the life course organization: A European perspective’, Canadian Journal of Ageing, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 441–464.

Hirsch, D. (2003) ‘Crossroads After 50: Improving Choices in Work and Retirement’, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, London.

Vickerstaff, S., Baldock, J., Cox, J. and Keen, L. (2004) ‘Happy Retirement? The Impact of Employers’ Policies and Practice on the Process of Retirement’, The Policy Press, London.

Banks, J. and Smith, S. (2006) ‘Retirement in the UK’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 40–56.

Gendell, M. and Siegel, J. S. (1992) ‘Trends in retirement age by sex, 1950–2005’, Monthly Labor Reivew, Vol. 115, No. 7, pp. 22–29.

Disney, R., Emmerson, C. and Wakefield, M. (2003) ‘Ill health and retirement in Britain: A panel data based analysis’, Institute of Fiscal Studies Working Papers, W03/02.

Gough, O. (2002) ‘Factors that influence voluntary and involuntary retirement’, Pensions, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 252–264.

Meadows, P. (2003) ‘Retirement ages in the UK: A review of the literature’, DTI –Employment Relations Research Series, No. 18.

UK Data from University of Essex Institute for Social and Economic Research (2004) British Household Panel Survey; Waves 1–12, 1991–2003, UK Data Archive, Colchester, Essex, June 2004, SN: 4967.

Bank of Italy website: www.bancaditalia.it.

GAD (2003) ‘Occupational Pension Schemes 2000’, Eleventh survey by the Government Actuary, The Government Actuary’s Department, London.

Inglese, L. (2003) ‘Early retirement in Italy: Recent trends’, Labour, Vol. 17 (Special Issue), pp. 175–207.

Kapteyn, A. and Panis, C. (2005) ‘Institutions and saving for retirement: Comparing the United States, Italy, and the Netherlands’, in Wise, D.A. (ed.) ‘Analyses in the Economics of Aging’, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Blöndhal, S. and Scarpetta, S. (1998) ‘The retirement decision in OECD countries’, OECD Economics Department Working Papers 202, OECD, Paris.

Brugiavini, A. and Peracchi, F. (2004) ‘Micro-modelling of retirement behaviour in Italy’, in Gruber, J. and Wise, D. A. (eds.) ‘Social Security Programs and Retirement around the World: Micro Estimation’, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Contini, B. and Fornero, E. (2003) ‘Labour and retirement choices of the elderly in Italy’, Mimeo, Centre for Research on Pensions and Welfare Policies, http://cerp.unito.it.

Franco, D. (2002) ‘A never ending pension reform’, in Feldstein, M. and Siebert, H. (eds.) ‘Social Security Pension Reform in Europe’, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Poterba, J. M., Venti, S. F. and Wise, D. A. (1994) ‘Targeted retirement saving and the net worth of elderly Americans’, American Economic Review, Vol. 84, No. 2, pp. 180–185.

Bernheim, B. D., Forni, L., Gokhale, J. and Kotlikoff, L. J. (2000) ‘How much should Americans be saving for retirement?’ American Economic Review, Vol. 90, No. 2, pp. 288–292.

Saunders, P., Bradbury, B. and Whiteford, P. (1989) ‘Unemployment benefit replacement rates’, Economic Analysis and Policy, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 1–28.

Bradshaw, J. and Piachaud, D. (1980) ‘Child Support in the European Community’, Bedford Square Press, London.

Bolderson, H. (1988) ‘Comparing social policies: Some problems of method and the case of social security benefits in Australia, Britain and the USA’, Journal of Social Policy, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 267–288.

Miles, D. and Iben, A. (2000) ‘The reform of pension systems: Winners and losers across generations in the United Kingdom and Germany’, Economica, Vol. 67, No. 266, pp. 203–228.

Herbertsson, T. T. (2001) ‘The economics of early retirement’, Journal of Pensions Management, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 326–335.

Johnson, R. (2000) ‘The effect of old-age insurance on male retirement: Evidence from historical cross-country data’, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Research Working Paper, No. 00-09.

Cremer, H. and Pestieau, P. (2000) ‘Reforming our pension system; Is it a demographic, financial or political problem?’ European Economic Review, Vol. 44, No. 4–6, pp. 974–983.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

1has a PhD in Pensions, she is the Head of the Finance and Business Law Department at the Westminster Business School and the Director of the Pension Investment Academy. Orla has published numerous articles and has wide experience of pension matters.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gough, O., Adami, R. & Waters, J. The effects of age and income on retirement decisions: A comparative analysis between Italy and the UK. Pensions Int J 13, 167–175 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/pm.2008.12

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/pm.2008.12