Abstract

The sweeping victories of Euroskeptic and far right parties in the 2014 European Parliament elections reflect public discontent with the European Union that has been growing since the beginning of the great recession. Using data from Eurobarometer 71.3 (Summer 2009), which were collected soon after the onset of the economic crisis, we test a conditional hypothesis derived from a combination of utilitarian theories of political support and social-identity theory. Specifically, we examine the extent to which the effects of individuals’ economic perceptions on their support for the EU are conditioned by the way they conceive of their national and EU identities. The analysis reveals that sociotropic rather than egocentric economic evaluations tend to drive EU support among people with stronger attachments to the nation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Bruno Waterfield, Henry Samuel, Fiona Govan, and Tom Kington. “European Elections 2014: EU Citizens Vote Against Immigrants, Austerity and Establishment,” The Telegraph, 25 May 2014.

Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks, “Calculation, Community and Cues: Public Opinion on European Integration,” European Union Politics 6 (December 2005): 419–43.

Christopher J. Anderson, “When in Doubt, Use Proxies: Attitudes Toward Domestic Politics and Support for European Integration,” Comparative Political Studies 31 (October 1998): 572.

Anderson, “When in Doubt”; Mark Franklin, Michael Marsh, and Lauren McLaren, “Uncorking the Bottle: Popular Opposition to European Unification in the Wake of Maastricht,” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 32 (December 1994): 455–72; Sylvia Kritzinger, “The Influence of the Nation-State on Individual Support for the European Union,” European Union Politics 4 (June 2003): 219–41; Leonard Ray, “Reconsidering the Link Between Incumbent Support and Pro-EU Opinion,” European Union Politics 4 (September 2003): 259–79.

Anderson, “When in Doubt,” 577.

Ignacio Sanchez-Cuenca, “The Political Basis of Support for European Integration,” European Union Politics 1 (June 2000): 151.

Franklin, Marsh, and McLaren, “Uncorking.”

Sanchez-Cuenca, “The Political Basis”; Thomas Christin, “Economic and Political Basis of Attitudes towards the EU in Central and East European Countries in the 1990s,” European Union Politics 6 (March 2005): 29–57; Robert Rohrschneider, “The Democracy Deficit and Mass Support for an EU-wide Government,” American Journal of Political Science 46 (April 2002): 463–75.

David Sanders, Paolo Bellucci, Gábor Tóka, and Mariano Torcal, The Europeanization of National Polities?: Citizenship and Support in a Post-Enlargement Union (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Sanders et al., Europeanization, 228.

Richard C. Eichenberg and Russell J. Dalton, “Europeans and the European Community: the Dynamics of Public Support for European Integration,” International Organization 47 (1993): 507–34; Matthew Gabel and Harvey D. Palmer, “Understanding Variation in Public Support for European Integration,” European Journal of Political Research 27 (1995): 3–19; Matthew Gabel and Guy D. Whitten, “Economic Conditions, Economic Perceptions, and Public Support for European Integration,” Political Behavior 19 (1997): 81–96; Matthew Gabel, “Public Support for European Integration: an Empirical Test of Five Theories,” Journal of Politics 60 (1998): 333–54; Vincent A. Mahler, Bruce J. Taylor, and Jennifer R. Wozniak, “Economics and Public Support for the European Union: An Analysis at the National, Regional, and Individual Levels,” Polity (2000): 429–53.

Anthony Downs, An Economic Theory of Democracy (New York: Harper & Row, 1957).

Christopher J. Anderson and Karl C. Kaltenthaler, “The Dynamics of Public Opinion Toward European Integration, 1973–93,” European Journal of International Relations 2 (June 1996): 175–99; Eichenberg and Dalton, “Europeans.”

Eichenberg and Dalton, “Europeans,” 522.

Anderson and Kaltenthaler “Dynamics of Public Opinion”; Eichenberg and Dalton, “Europeans and the European Community”; Adam P. Brinegar, Seth K. Jolly, and Herbert Kitschelt, “Varieties of Capitalism and Political Divides Over European Integration,” in European Integration and Political Conflict, ed. Gary Marks and Marco R. Steenbergen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 62–89.

Gabel and Palmer, “Understanding Variation.”

Sean Carey, “Undivided Loyalties: Is National Identity an Obstacle to European Integration?” European Union Politics 3 (December 2002): 387–413; Gabel and Palmer, “Understanding Variation”; Lauren M. McLaren, “Opposition to European Integration and Fear of Loss of National Identity: Debunking a Basic Assumption Regarding Hostility to the Integration Project,” European Journal of Political Research 43 (2004): 895–912; John Garry and James Tilley, “The Macroeconomic Factors Conditioning the Impact of Identity on Attitudes Towards the EU,” European Union Politics 10 (August 2009): 361–79.

Christin, “Economic and Political Basis”; Orla Doyle, “Unraveling Voters’ Perceptions of the Economy” (University College Dublin Geary Institution Discussion Paper Series, 2010); Gabel and Whitten, “Economic Conditions”; Steffen Mau, “Europe From the Bottom: Assessing Personal Gains and Losses and Its Effects on EU Support,” Journal of Public Policy 25 (October 2005): 289–311.

Mau, “Europe From the Bottom,” 303.

Bernd Hayo and Wolfgang Seifert, “Subjective Economic Well-Being in Eastern Europe,” Journal of Economic Psychology 24 (June 2003): 329–48.

Lauren M. McLaren, “Public Support for the European Union: Cost/Benefit Analysis or Perceived Cultural Threat?” Journal of Politics 64 (2002): 551–66, at 555.

Carey, “Undivided Loyalties.”

McLaren, “Public Support,” 551.

Ronald Inglehart, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977).

Sanders et al., The Europeanization of National Polities?

Naomi Levy, “Measuring Multiple Identities: What is Lost with a Zero-Sum Approach,” Politics, Groups, and Identities (forthcoming).

Juan Diez Medrano and Paula Gutiérrez, “Nested Identities: National and European Identity in Spain,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 24 (January 2001): 753–78.

Jack Citrin and John Sides, “More Than Nationals: How Identity Choices Matter in the New Europe,” in Transnational Identities: Becoming European in the EU, ed. Richard K. Hermann, Thomas Risse, and Marilynn Brewer (New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2004), 161–85.

Dieter Fuchs and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Cultural Diversity, European Identity and the Legitimacy of the EU (Cheltenham and Camberley, UK, and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2011), 30.

Gary Marks, “Territorial Identities in the European Union,” in Regional Integration and Democracy: Expanding on the European Experience, ed. Jeffrey Anderson (New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999), 69–91.

Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks, “Does Identity or Economic Rationality Drive Public Opinion on European Integration?” Political Science and Politics 37 (2004): 415–20, at 416.

Henri Tajfel and John C. Turner, “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, ed. William G. Austin and Stephen Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole, 1979), 33–47.

Rupert Brown, Group Processes: Dynamics Within and Between Groups (Oxford: Blackwell, 1988).

Michael Billig and Henri Tajfel, “Social Categorization and Similarity in Intergroup Behaviour,” European Journal of Social Psychology 3 (1973): 27–52; Michael Diehl, “The Minimal Group Paradigm: Theoretical Explanations and Empirical Findings,” European Review of Social Psychology 1 (1990): 263–92; Henri Tajfel, Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

Catherine E. de Vries and Kees Van Kersbergen, “Interests, Identity and Political Allegiance in the European Union,” Acta Politica 42 (July 2007): 307–28.

Garry and Tilley, “The Macroeconomic Factors”; Robert Rohrschneider and Matthew Loveless, “Macro Salience: How Economic and Political Contexts Mediate Popular Evaluations of the Democracy Deficit in the European Union,” Journal of Politics 72 (October 2010): 1029–45.

Garry and Tilley, “The Macroeconomic Factors,” 367.

This wave of the Eurobarometer is the only one with the particular constellation of survey items that we need to test our hypotheses.

Hajo G. Boomgaarden, Andreas R.T. Schuck, Matthijis Elenbaas, and Claes H. De Vreese, “Mapping EU Attitudes: Conceptual and Empirical Dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU Support,” European Union Politics 12 (June 2011): 241–66.

Sanders et al., The Europeanization of National Polities?

This scale’s Chronbach’s alpha, at 0.776, is quite respectable.

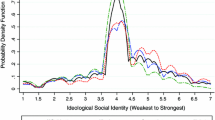

The original battery yielded so little variation on the attachment to the nation item that the battery does not allow researchers to distinguish between ardent nationalists and those who are patriotic, but less nationalistic. Our relational measure of identity gauges the extent to which individuals’ attachment to the nation is exclusive.

Our relational measure of identity does not allow us to distinguish between those with equally weak attachment to both entities and those with equally strong attachments to them. However, there is little variation in the absolute levels of attachment. Over 70 percent of those with equal levels of attachment professed they felt both European and national “to a great extent,” and roughly 25 percent felt both European and national “somewhat.” Fewer than 5 percent of respondents felt little or no attachment to either entity.

Adrian Favell, Eurostars and Eurocities: Free Movement and Mobility in an Integrating Europe (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008).

Although the data are hierarchical in nature, with individuals nested within countries, we estimate the models using OLS regression with cluster-robust standard errors, rather than a multilevel modeling approach. Our approach requires fewer assumptions and is unbiased as long as no cross-level interactions are included in the model.

We also ran the model with controls for inflation rate and GDP growth, but found that neither was statistically significant and that their omission did not affect the other estimates. We therefore chose to present the more parsimonious model.

We should not be surprised at the size of this effect because the measure embeds attachment to the EU, which is closely related to the dependent variable.

Anderson, “When in Doubt, Use Proxies”; Lauren McLaren, “Explaining Mass-Level Euroscepticism: Identity, Interests, and Institutional Distrust,” Acta Politica 42 (July 2007): 233–51.

We also tested a variety of individual-level controls that we trimmed from the final model. They included immigration status, parental immigration status, and political ideology.

Wald tests comparing Models 1 and 3 and Models 2 and 4 returned highly statistically significant F-statistics of 38.7 (df: 2,23) and 49.7 (df: 2,11), respectively.

Thomas Brambor, William Roberts Clark, and Matt Golder, “Understanding Interaction Models: Improving Empirical Analyses,” Political Analysis 14 (May 2005): 63–82.

Because few respondents expressed a stronger attachment to the EU than to the nation, the estimated effects at the EU-oriented end of the scale should be interpreted cautiously. It is possible that the observed results are an artifact of the linear model.

The median sociotropic economic evaluation is 0.25, while the median egocentric economic evaluation is 0.75.

When sociotropic economic evaluation is set at 1 and egocentric economic evaluation is set at 0, the effect of identity orientation on EU support is no longer statistically significant. However, there are only 30 individuals who have strong positive evaluations of the national and negative evaluations of their household finances.

Andrea Schlenker-Fischer, “Multiple Identities and Attitudes Towards Cultural Diversity in Europe: A Conceptual and Empirical Analysis” in Cultural Diversity, ed. Fuchs and Klingemann, 110.

For reviews see Leif Lewin, Self Interest and Public Interest in Western Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991); D. Roderick Kiewiet and Michael S. Lewis-Beck, “No Man Is an Island: Self-Interest, the Public Interest, and Sociotropic Voting,” Critical Review 23 (2011): 303–319; Michael S. Lewis-Beck and Mary Stegmaier, “Economic Determinants of Electoral Outcomes,” Political Science 3 (2000): 183–219.

Gerald H. Kramer, “Short-Term Fluctuations in US Voting Behavior, 1896–1964,” American Political Science Review 65 (1971): 131–43.

Donald R. Kinder and D. Roderick Kiewiet, “Sociotropic Politics: the American Case,” British Journal of Political Science 11 (1981): 129–61.

Gerald H. Kramer, “The Ecological Fallacy Revisited: Aggregate-Versus Individual-Level Findings on Economics and Elections, and Sociotropic Voting,” American Political Science Review 77 (1983): 92–111; Douglas A. Hibbs, “Solidarity or Egoism?” (Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 1993).

Geoffrey Evans and Robert Andersen, “The Political Conditioning of Economic Perceptions,” Journal of Politics 68 (2006): 194–207.

Kiewiet and Lewis-Beck, “No Man Is an Island,” 315.

Fuchs and Klingemann, Cultural Diversity; Fritz Scharpf, Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

David Easton, “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support,” British Journal of Political Science 5 (1975): 435–57.

Kiewiet and Lewis-Beck, “No Man Is an Island.”

There might also be downsides to the timing of the survey, as the almost universal acknowledgement of poor economic conditions might affect the results. It is likely that this reduced variation in economic views reduces the power of hypothesis tests of the effects of sociotropic economic evaluations on EU support. It is unclear, however, what effect, if any, the nearly universal acknowledgement of poor economic conditions has on the conditioning effect of identity. Further studies should investigate whether our results hold during periods with a greater range of sociotropic economic evaluations.

Lewin, Self Interest and Public Interest.

Kinder and Kiewiet, “Sociotropic Politics”; Kiewiet and Lewis-Beck, “No Man Is an Island.”

Kramer, “The Ecological Fallacy Revisited.”

Hooghe and Marks, “Calculation, Community and Cues.”

Garry and Tilley, “The Macroeconomic Factors.”

de Vries and Van Kersbergen, “Interests, Identity and Political Allegiance.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

The authors wish to thank Ben Bowyer, Liesbet Hooghe, John Sides, Boyka Stefanova, two anonymous reviewers, and the editors of Polity for their helpful suggestions and comments.

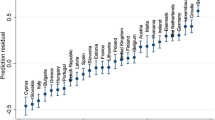

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levy, N., Phan, B. The Utility of Identity: Explaining Support for the EU after the Crash. Polity 46, 562–590 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/pol.2014.19

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/pol.2014.19