Abstract

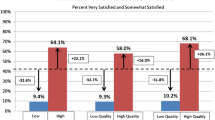

This article investigates possible sources of error in a public opinion survey conducted by a metropolitan police service. Logistic regression models are used to analyse the results of a mixed-mode survey in which respondents were questioned over the telephone or through a Web survey. Even after controlling for demographics, respondent lifestyle and criminal victimization, Web respondents were significantly more likely to (i) give lower scores on questions about satisfaction with the police and level of perceived police legitimacy, (ii) indicate unfavourable opinions about the police, (iii) confess worries or fear about their own security and (iv) select moderate response choices. Telephone surveys seem to overestimate favourable opinions about the police and underestimate public concerns about security. It is important to understand these effects because survey results are often used to support strategic decisions about public safety or to assess police performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While sampling bias or the failure to target a representative portion of the population is now well-recognized (for example, Berk, 1983) and thus not discussed here, nonresponse error is a methodological threat even if the base sample is correctly selected. A study that managed to contact a representative sample of respondents would still yield representative results only if all respondents completed the survey and gave truthful answers.

Households with mobile phones only are therefore excluded from the first sampling frame, which could result in coverage error (Busse and Fuchs, 2012). Subsequent analyses take this issue into account by controlling for demographics.

The computation of comparable response rates for different modes of collection is difficult (Shih and Fan, 2008). For telephone, most firms use a simple computation (number of respondents/number of answered calls). For Web surveys, although firms are generally not able to determine the number of people who actually received an invitation, Web response rates are often calculated by dividing the number of respondents by the number of invitations sent.

Multivariate analyses were also conducted. Telephone respondents refused to respond to a larger number of questions (Poisson regression; P<0.01), and a greater number of telephone respondents refused to answer at least one of the seven questions (binary logistic regression; P<0.01) controlling for demographics.

An anonymous reviewer highlighted the fact that the temporal priority of the two variables is not defined: it is almost certain that individuals go out at night because they believe it is safe to do so. There is a statistically significant relationship between both variables (r=0.313; P<0.01). However, in this analysis, the frequency of nights out is used as a control variable measuring exposure to risk. Individuals who go out at night expose themselves to higher risks of victimization, which could influence their perception of safety.

References

Baumgartner, H. and Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M. (2001) Response styles in marketing research: A cross-national investigation. Journal of Marketing Research 38(2): 143–156.

Berk, R.A. (1983) An introduction to sample selection bias in sociological data. American Sociological Review 48(3): 386–398.

Brandl, S.G., Frank, J., Worden, R.E. and Bynum, T.S. (1994) Global and specific attitudes toward the police: Disentangling the relationship. Justice Quarterly 11(1): 119–134.

Brown, B. and Benedict, W.R. (2002) Perceptions of the police: Past findings, methodological issues, conceptual issues and policy implications. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 25(3): 543–579.

Brunton-Smith, I. and Sturgis, P. (2011) Do neighborhoods generate fear of crime? An empirical test using the British crime survey. Criminology 49(2): 331–369.

Busse, B. and Fuchs, M. (2012) The components of landline telephone survey coverage bias: The relative importance of no-phone and mobile-only populations. Quality and Quantity 46(4): 1209–1225.

Chang, L. and Krosnick, J.A. (2009) National surveys via RDD telephone interviewing versus the internet: Comparing sample representativeness and response quality. Public Opinion Quarterly 73(4): 641–678.

Chang, L. and Krosnick, J.A. (2010) Comparing oral interviewing with self-administered computerized questionnaires: An experiment. Public Opinion Quarterly 74(1): 154–167.

Collier, P.M. (2006) In search of purpose and priorities: Police performance indicators in England and Wales. Public Money and Management 26(3): 165–172.

De Leeuw, E.D., Hox, J.J. and Dillman, D. (eds.) (2008) Mixed-mode surveys: When and why. In: International Handbook of Survey Methodology. New York: Psychology Press (Taylor and Francis Group), pp. 299–316.

Dillman, D. and Messer, B.L. (2010) Mixed-mode surveys. In: P.V. Marsden and J.D. Wright (eds.) Handbook of Survey Research. Bingley, UK: Emerald, pp. 551–574.

Dillman, D. et al (2009) Response rate and measurement differences in mixed-mode surveys using mail, telephone, interactive voice response (IVR) and the internet. Social Science Research 38(1): 1–17.

Dillman, D., Smyth, J. and Christian, L. (2008) Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. New York: Wiley.

Dillman, D.A., Eltinge, J., Groves, R.M. and Little, R.J.A. (2002) Survey nonresponse in design, data collection, and analysis. In: R.M. Groves, D.A. Dillman, J. Eltinge and R.J.A. Little (eds.) Survey Nonresponse. New York: Wiley-Interscience, pp. 3–25.

Donnelly, M., Kerr, N.J., Rimmer, R. and Shiu, E.M. (2006) Assessing the quality of police services using SERVQUAL. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 29(1): 92–105.

Doran, B.J. and Burgess, M.B. (2012) Putting Fear of Crime on the Map: Investigating Perceptions of Crime using Geographic Information Systems. New York: Springer eBooks.

Drake, L.M. and Simper, R. (2005) The measurement of police force efficiency: An assessment of U.K. Home Office policy. Contemporary Economic Policy 23(4): 465–482.

Farrall, S., Bannister, J., Ditton, J. and Gilchrist, E. (1997) Questioning the measurement of the ‘fear of crime’: Findings from a major methodological study. The British Journal of Criminology 37(4): 658–679.

Ferraro, K.F. and LaGrange, R. (1987) The measurement of fear of crime. Sociological Inquiry 57(1): 70–97.

Fricker, S., Galesic, M., Tourangeau, R. and Yan, T. (2005) An experimental comparison of web and telephone surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly 69(3): 370–392.

Greene, J., Speizer, H. and Wiitala, W. (2008) Telephone and web: Mixed-mode challenge. Health Services Research 43(1): 230–248.

Groves, R.M., Fowler Jr, F.J., Couper, M.P., Lepkowski, J.M., Singer, E. and Tourangeau, R. (2004) Survey Methodology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience.

Hale, C. (1996) Fear of crime: A review of the literature. International Review of Victimology 4(2): 79–150.

Hennigan, K.M., Maxson, C.L., Sloane, D. and Ranney, M. (2002) Community views on crime and policing: Survey mode effects on bias in community surveys. Justice Quarterly 19(3): 565–587.

Jäckle, A., Roberts, C. and Lynn, P. (2010) Assessing the effect of data collection mode on measurement. International Statistical Review 78(1): 3–20.

Kalton, G. and Schuman, H. (1982) The effect of the question on survey responses: A review. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A (General) 145(1): 42–73.

Lensvelt-Mulders, G. (2008) Surveying sensitive topics. In: E.D. de Leeuw, J.J. Hox and D. Dillman (eds.) International Handbook of Survey Methodology. New York: Psychology Press (Taylor and Francis Group), pp. 461–478.

Messer, B.L., Edwards, M.L. and Dillman, D. (2012) Determinants of Item Nonresponse to Web and Mail Respondents in Three Address-based Mixed-mode Surveys of the General Public. Washington DC: Washington State University.

Sakshaug, J.W., Yan, T. and Tourangeau, R. (2010) Nonresponse error, measurement error, and mode of data collection: Tradeoffs in a multi-mode survey of sensitive and non-sensitive items. Public Opinion Quarterly 74(5): 907–933.

Shih, T.-H. and Fan, X. (2008) Comparing response rates from web and mail surveys: A meta-analysis. Field Methods 20(3): 249–271.

Skogan, W.G. (2006) The promise of community policing. In: D. Weisburd and A.A. Braga (eds.) Police Innovation: Contrasting Perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 27–42.

Tourangeau, R. and Yan, T. (2007) Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin 133(5): 859–882.

Wall, D.S. (2013) Policing identity crimes. Policing & Society 23(4): 437–460.

Weisburd, D. and Eck, J.E. (2004) What can police do to reduce crime, disorder, and fear? The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 593(1): 42–65.

Weitzer, R. and Tuch, S.A. (2005) Determinants of public satisfaction with the police. Police Quarterly 8(3): 279–297.

Ye, C., Fulton, J. and Tourangeau, R. (2011) More positive or more extreme? A meta-analysis of mode differences in response choice. Public Opinion Quarterly 75(2): 349–365.

Zhao, J.S., Lawton, B. and Longmire, D. (2010) An examination of the micro-level crime–fear of crime link. Crime and Delinquency, published online 10 November, doi: 10.1177/0011128710386203.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boivin, R., Cordeau, G. Do Web surveys facilitate reporting less favourable opinions about law enforcement?. Secur J 30, 335–348 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2014.35

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2014.35